Kris Pirmann walks through a high tunnel at his farm in rural Johnson County, Ill. as the wind whips at the plastic sheets that arc over his head. The air inside the structure is warm and humid and gives Pirmann a head start to the growing season.

“We have turnips and beets, Swiss chard, carrots, radishes, three different types of bok choy,” Pirmann said. “Eventually we’ll have tomatoes trellised in here.”

Pirmann and his wife grow about 250 varieties of vegetables on their sustainable farm, and they want no part of hydraulic fracturing, the controversial fossil fuel extraction technique also known as fracking that injects water, sand and chemicals underground to crack shale deposits to release oil and natural gas.

Voters in Johnson County, Ill. will vote Tuesday on a proposition to ban fracking. Even though it is non-binding, the proposition is driving a rift between people in this scenic southern Illinois county. The state passed a law last year to regulate fracking, working with industry and environmental groups, but some groups in southern Illinois feel they were left out of the process.

Fracking opponents like Pirmann say they have to rely on word-of-mouth to grow their support.

“It seems like we’re David versus Goliath, but I just think that if the discussion was out there openly addressed that a lot people would open their eyes to what I think is really going on,” Pirmann said.

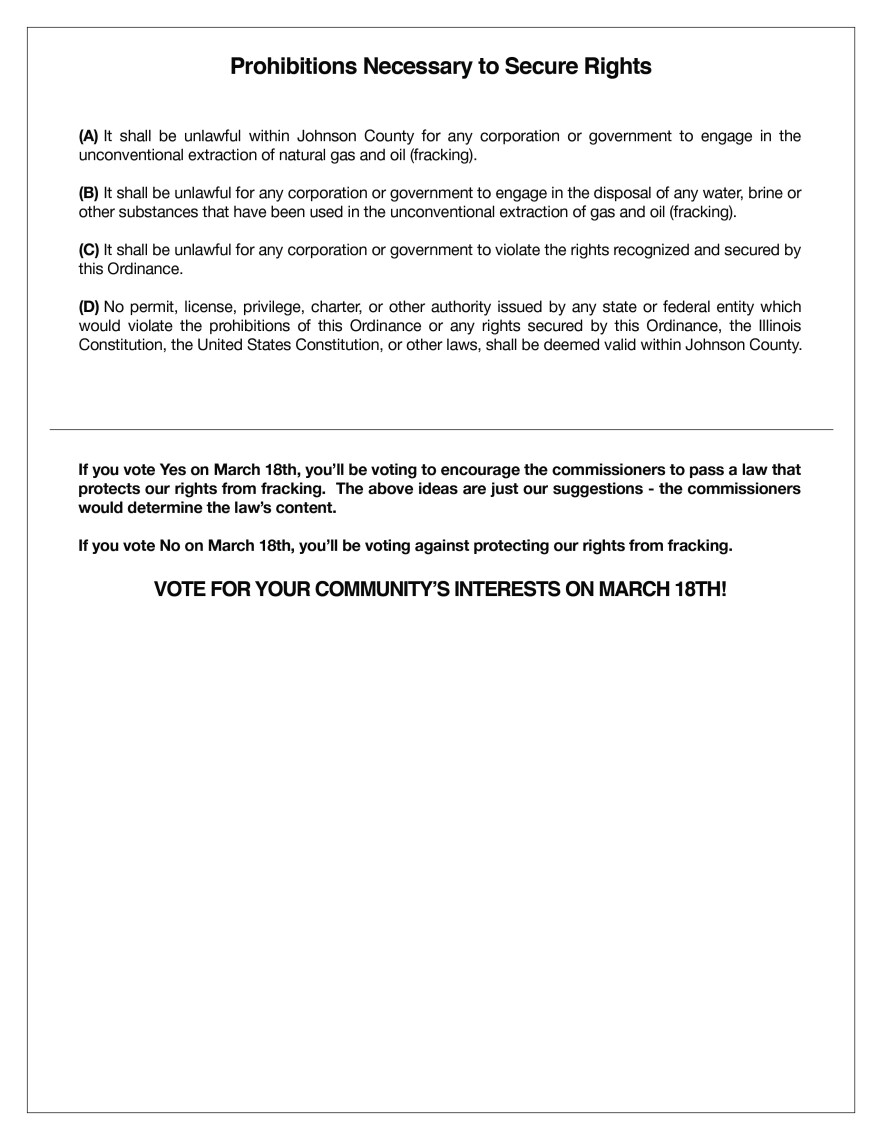

Fracking opponents have help from the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund, or CEDLF. A CEDLF organizer is working with fracking opponents to get people to vote YES and present a so-called “Community Bill of Rights” to the county board if it is successful.

At least one member of the county board is campaigning against this referendum, and the Illinois Chamber of Commerce contributed $23,500 dollars to proposition opponents. Residents are receiving robo calls and mailers while listening to radio ads to encourage folks to vote against the ballot initiative.

And the county’s only newspapers - The Vienna Times and Goreville Gazette - no longer publish fracking opponents’ ads.

That led Goreville Gazette editor Joe Rehana to quit.

“I felt the situation was a little bit unethical and at that point I felt it was a little bit uncalled for because the county already had plenty of questions about this subject and it just felt as if what we were doing was removing the ability to answer those questions,” Rehana said.

Proposition opponents argue the entire referendum was instigated by outside groups, pointing their fingers directly at CELDF. Mitch Garrett owns and operates Shawnee Professional Services, and he is one of the leading voices against the non-binding ballot initiative.

“The effort has confused our people and turned people against each other for no reason,” Garrett said. “It is also bad because it distracts people from doing things that can be done. People are wasting their time lobbying the county board, asking them to do something that the county board cannot do.”

"Shall the people's right to local self-government be asserted by Johnson County to ban corporate fracking as a violation of their rights to health, safety, and a clean environment?" A YES vote means one is in favor of banning fracking. A NO vote is against the fracking ban.

Garrett and other opponents say a ban will open Johnson County up for costly lawsuits from oil and gas companies that they would most likely lose.

Garrett stresses he is not necessarily pro-fracking. In fact, he turned down a lease on his 75 acres. He thinks the referendum is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Pointing to other CELDF ordinances, he believes this “Community Bill of Rights” would be profoundly anti-business.

“If it were a simply opinion poll about what the people feel about fracking, then it would have been worded in a different way,” Garrett said.

This is part of the problem for Carol Gerdes. Speaking at a park in Goreville, Gerdes is no fan of fracking and she leans towards voting YES. Still, she is not entirely sure because the wording is confusing.

“I feel like I need to read and understand a little bit more. And I really don’t know what’s legal and what’s not as far as this referendum,” Gerdes said.

Gerdes just wants what is best for Johnson County, and said she would rather see people slow down and think things through.